Taking the Transit Hub from Development to Destination

It’s unlikely that today’s harried commuter thinks of their local tube stop as awe-inspiring or elegantly designed. But the stations of old were very much cathedrals of transportation—so much so that their architecture continues to be revered, earning the nickname “destistation.” Located in city centres, they were buildings to be admired rather than simply passed through.

This all changed as increasing numbers of workers began commuting from further distances, and the need for light-rail stations in “fringe” areas was met with bare bones, merely functional facilities with an emphasis on efficiency rather than aesthetics. These stations did, however, become catalysts for another kind of change: beginning with low-density housing that steadily increased in intensity, the surrounding areas became satellite cities where residents needed more than just roofs over their heads—they needed amenities, entertainment and employment.

Beyond serving simply as links connecting urban centres—and often fracturing neighbourhoods as they cut through them—these new stations were planned as development catalysts and partially responsible for the skyrocketing value of transit-linked real estate. Examples of this transit-oriented development approach include “Metro-Land” and suburban development in northwest London, as well as MTR’s station area developments around the edges and in the city centre of Hong Kong, such as Telford Gardens and the International Finance Centre.

Fast forward to the present day, where well-planned transit has become the holy grail of sustainable urban planning and the connection between public transportation and development is firmly established in the minds of transit authorities, developers and government. With the level of investment in transit-oriented development in the UK at unprecedented levels (£15 billion on Crossrail 1 in London, £40 billion on HS2 and an estimated £27 billion for Crossrail 2, just to name a few) the question on everyone’s mind is this: how do we maximize value and return on investment? And in particular, how do we leverage this investment to not only deliver monetary returns but address the social and housing crises faced by our cities?

For CallisonRTKL, the question sounds more like this: how do we move from transit-oriented development to mobility-oriented destinations? How do we shift the focus from accessibility to urban, economic and social value? The answer: place making combined with a well-designed consumer experience.

Embracing a New Philosophy: MODe

To realize maximum value from new developments, we must think of transit as more than a system that gets people from point A to point B. Rather than being concerned only with departure and arrival, we consider what happens before departure and after arrival. This is what CallisonRTKL calls mobility-oriented development (MODe).

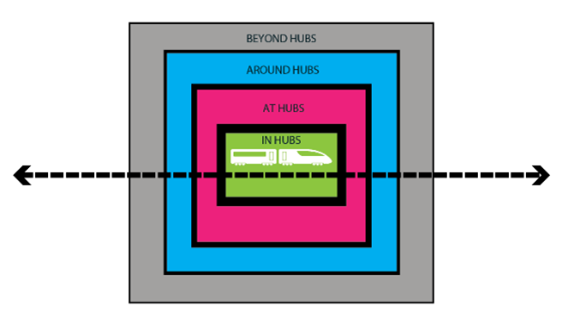

MODe looks at the user experience not only in the station, but at the station, around it and beyond it. Inside, tailored routes, easy navigation, abundant connections and frequency of service are obvious goals, but offering a mix of personal and business services, entertainment and exhibits, retail, food and beverage and other conveniences injects life into the station. Next, look outside. What else is offered on-site? Are there residential flats on top of the station? Are there direct connections to other modes of transit? What about educational or sports facilities?

Out to the next rung: in the area around the station, we evaluate short, medium and long-distance connectivity to other sites; density and sustainability; the quality and quantity of live, work and play components, including educational and cultural offerings; and economic development in the form of office and retail.

Finally, zoom out to the bird’s eye view, and consider the station’s role in the larger community. How does it impact stakeholder prosperity, well-being, social cohesion and economic opportunity? How does it impact the urban environment?

Meaningful Metrics: MODex

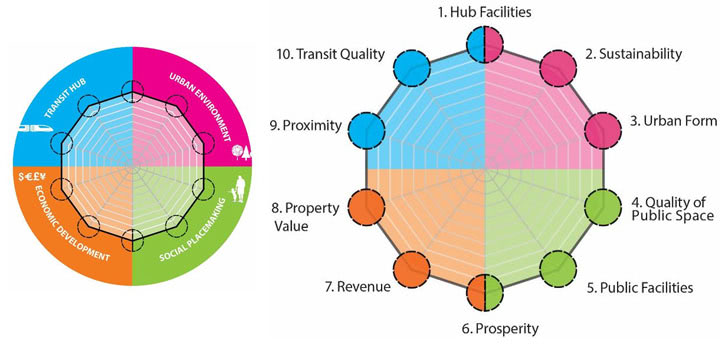

To simplify it, we break the evaluation down into four indicators: transit, urban, economic and social. CallisonRTKL calls this set of indicators MODex (mobility oriented development index): common parameters, each with their own set of variables, for evaluating the potential and the performance of transit hub development.

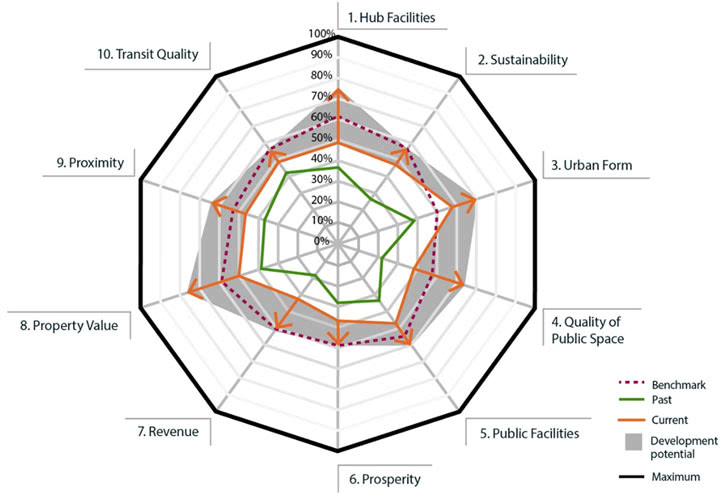

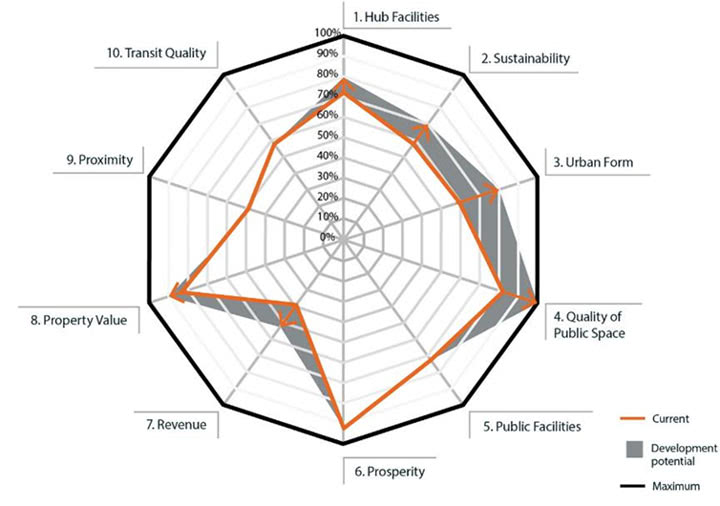

The system is straightforward but powerful in that it measures the score of the development against benchmarks set by similar stations and pinpoints areas for possible improvement, presenting the data in a simple yet clear format that is easy to understand and use.

Take, for example, a station with which UK residents, visitors—and Harry Potter fans around the world—are familiar: Kings Cross. The 67-acre site surrounding the revamped historic station is undergoing a major redevelopment effort that aims to shape and improve a new public realm and create a new sense of place.

Kings Cross is a successful “classic regeneration challenge” according to the Urban Land Institute case study. Yet there is room for improvement with regard to sustainability, quality of public space, and other areas, which MODex can help to identify and which we can use to inform the next tranche of mobility-oriented developments:

With major and not-so-major cities around the world continuing to densify at breakneck pace, our transit stations and the development around them must keep up. The next generation of transit views the traveler as a consumer to be pleased rather than a captive audience and the city as an interconnected entity shaped with human-centric design in mind. To extract the highest value from transit-oriented development, design tools like MODex can help ensure that designs are aligned with the economic, environmental and social aspirations and make a major difference to our cities and our quality of life.

We need to make the station a place; we need to make it a “destistation.”

Cover image via © User:Colin/Wikimedia Commons