Disrupting the Fundamentals: Changing the Rules of Infrastructure

At the recent 2017 APA National Planning Conference in New York City, CallisonRTKL released Urban Shift, a compilation of trends and influencers driving the design and development of modern cities along with key project examples. This post is the first in a series that takes Urban Shift a step further in exploring how urban planners can address the environmental, economic and social shifts taking place around the world.

If you aren’t a city planner or government official, the word “infrastructure” may not inspire much in the way of creativity. You might think of it as the great and powerful Oz of urban society: it shapes nearly everything we do and grants us our needs and desires, but most of us pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

Infrastructure gives us access to water and food; it generates our power; it ensures that roadways remain functional and that airports deliver passengers and goods from point A to point B. Each of these—the product of endless analysis, billions of dollars and years of effort—inhabit a space that rarely makes itself known over the course of our daily experience. Only when it breaks down or malfunctions do we take note of it and demand better.

But as we face a future of fundamental disruption in nearly every area of our lives—from optimized mobility to food resources, water scarcity and climate change—so too must our systems evolve to reshape and redefine urban life.

DO MORE WITH LESS

It’s no secret that urban populations are growing. In Australia, where I’m writing this, the populations of Sydney and Melbourne are expected to double in the next 30 years. In Sydney, that projection has spurred a quick study of larger cities like Chicago with its three airports, massive rail network and extensive water and wastewater management systems. In Melbourne, as in many cities, urban growth is now critically impinging on arable land, causing a direct conflict between two essential needs: affordable shelter and food security.

Cities have begun to assume the role of experimental laboratories, encouraging innovation in one city that can often serve as a model for others. For example, conservation education efforts enabled Los Angeles County to maintain the same level of water usage over the last five years, even as its population has risen by more than 1 million. Solar roofs have recently hit a cost-per-square-foot milestone that makes parity in pricing with traditional roofing appear imminent. Combined with the widespread use of domestic batteries, this could mean the upending of the power distribution economy. The increasing relevance of sustainable design practices and smart data management will help lessen the positive correlation between development and increased infrastructural burden.

BE FLEXIBLE

Infrastructure enables growth, but if incorrectly planned or sized, it can become an impediment to development, a drag on the economy and even a source of social unrest. Nowhere is this truer than in transit; no one likes endless road construction and sprawl, yet these persist as a staple of urban development.

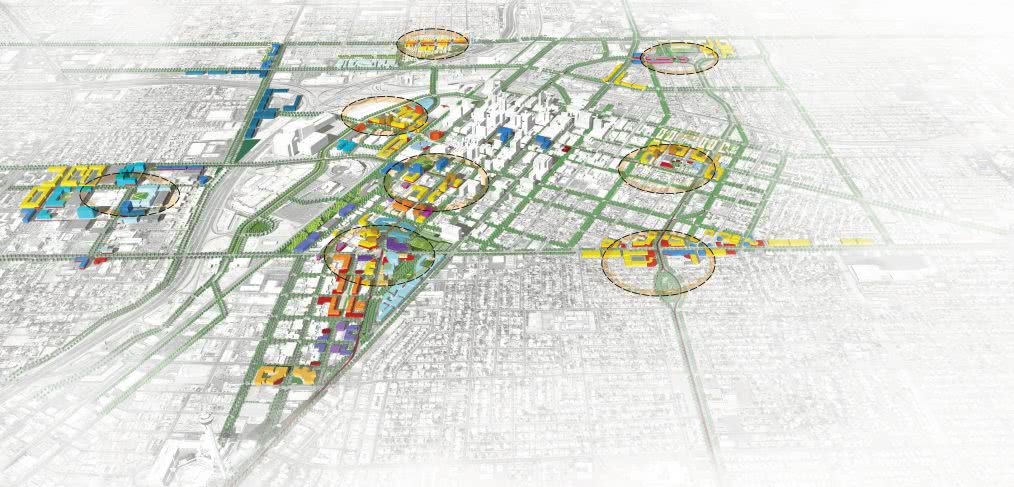

But solutions exist that have the power to remake urban landscapes. Layered street grids—a “tartan plaid” of streets—offer a mixed-use mobility system with rights of way dedicated to or prioritizing certain types of transport. CallisonRTKL’s master plan for Downtown Las Vegas is a good example: the design uses a layered street grid to tightly integrate transportation infrastructure with physical and economic planning, promoting the growth of a network of walkable, economically resilient districts. Combined with real-time traffic and data management, planning techniques like these may not get everyone out of their cars, but they will make cities safer for pedestrians, easier for cyclists and more efficient for everyone.

Similarly, intense interest in autonomous and electric vehicles and the “transportation as service” model all point to a time when the old guard of oil and gas is supplanted by a cleaner, greener constellation of industries serving more sustainable cities.

In the short term, less demand for parking space has inspired projects like Miami’s 1111 Lincoln Road—a high-performance structure with charging stations, ground-floor retail, restaurants, concierge and car share services, bike rental, art galleries and highly sought-after event spaces. In the long term, decommissioned roadways may find new life as linear parks or as connective tissue between cities and communities previously severed by overly zealous infrastructure building in decades past.

FROM BACKGROUND TO FOREGROUND

Acknowledging that we are part of, rather than separate from, our environment is crucial to creating meaningful community connections. One way to foster this understanding is to make infrastructure more apparent and more engaged. A bold example is the Amager Bakke waste-to-power incinerator plant in Copenhagen, which will sport the world’s longest man-made ski slope on its 440-meter-long roof.

Less ostentatious but no less significant are everyday urban interventions like bioswale networks, bike trails, an open city data feed highlighting resource usage and management, mid-block pedestrian lanes and PV canopies over parking garages. Even rezoning efforts that clear the way for buildings to be reused as apartments and offices open new opportunities to connect social and infrastructural endeavors.

There is no limit to the ideas—physical, regulatory, or cultural—that can position infrastructure to play a more active and visible role in our lives. And as we look at its potential to address modern-day challenges with fresh eyes, by reconsidering and giving infrastructure a larger role to play on the urban stage, we uncover possibilities for increasing our quality of life and strengthening the backbone of our communities.

Wow, I’m impressed. Great article Noam!