Airports and Community (Part I)

How have airports evolved over the years, and how will it inform the development of cities in the future? In this two-part series, Nate Cherry will offer an in-depth look at the vital relationship between airports and communities. Part one will focus on corridor-based growth and the emergence of airport cities.

The aviation scene is being turned on its head. Most elements of air travel we experience today were designed to serve the merely functional requirements of transport from one location to another. As our economy and culture have changed, airports, airlines and airplanes are being challenged by significantly greater customer expectations in how airports are supposed to function and what air travel means to society.

Studies show that the current model no longer works very well. We know that when we fly we get less sleep, eat less healthily, get less exercise and undergo increased stress levels. We’re also seeing an uptick in time constraints, adding to the difficulty of getting to and from the airport. Most terminals are not particularly well designed and can be quite limited in services – I often feel stranded on “airport island” – stuck without the hotels, workspaces, technology and amenities that I need to get work done.

To fill the gap between the airport and the user, there are upgrades needed to serve the changing economy and traveler. The ability to exchange ideas, become inspired and collaborate is where today’s real value is, and we can study progressive airports and cities that have begun to address these issues in interesting ways.

On The Go

In the initial days of airport evolution, a few entrepreneurs who were looking for cheap land and space to build saw the opportunity to do business near the airport. These people serviced a global clientele by designing, testing or manufacturing something to a time-based deadline.

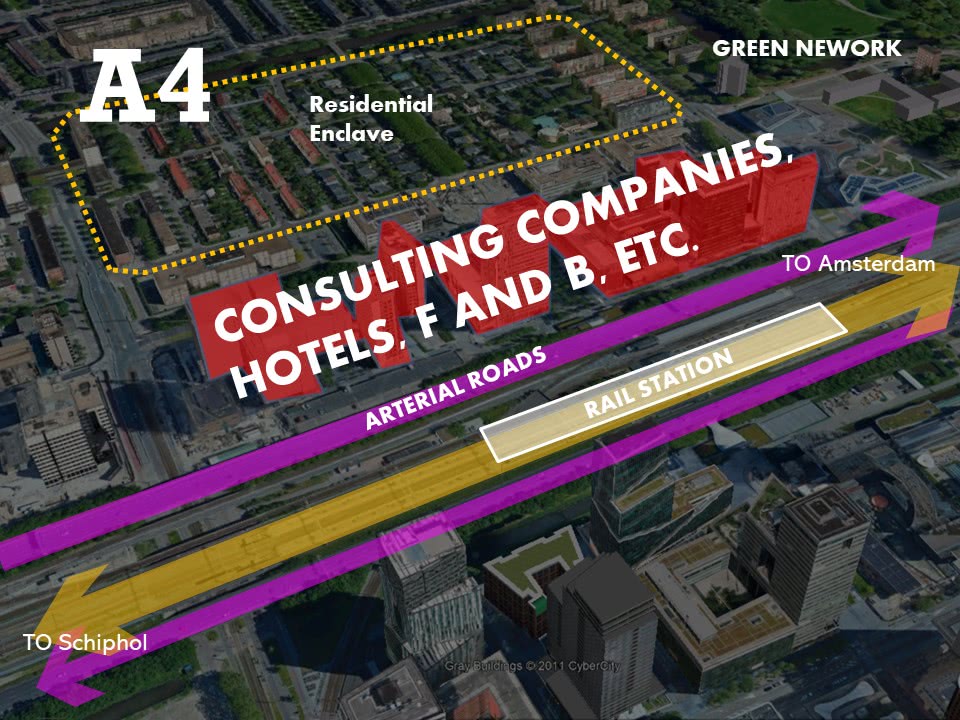

The aerospace industry, engineering companies and logistics companies saw early on the benefits of being close to an airport. Certain airports, such as Schiphol outside of Amsterdam (AMS), realized that the land use definition between downtown and the airport needed to be blurred. Businesses and entire industries wanted to be located along the corridor that serves both downtown and the airport.

Schiphol benefits from a variety of transportation options along its primary growth corridor, and the city sees the airport as a complementary and noncompetitive district that supports the downtown Amsterdam economy. In fact, several office and retail uses along the A4 corridor feature larger plate formats which prevent them from being located in downtown.

What distinguishes Schiphol is the airport’s commitment to multimodal mobility along the corridor — the many trains, buses and bikeways, all of which play a role in improving someone’s ability to get around. Additionally, Schiphol has invested a tremendous amount in the airport to become a business destination unto itself, ranging from club memberships to business-related services such as co-working, fitness center, hotel and dining available to club members.

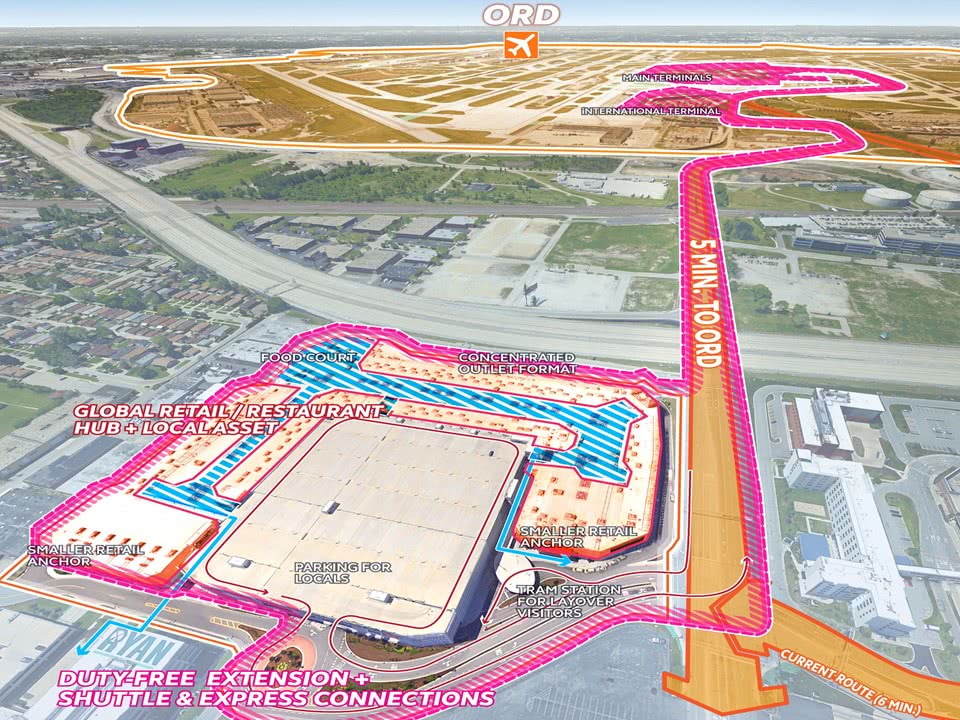

Similarly, in Chicago, many Fortune 500 companies have long located outside the city center along primary corridors connecting O’Hare (ORD). To serve workers, visitors and nearby residents, developments are quickly cropping up, such as the fashion outlets of Chicago.

“ORD and the Fashion Outlets of Chicago have a strong relationship; one would not exist without the other. We also find that a lot of locals from both the city and suburbs are coming to shop here as well. It’s becoming a gathering place for the area,” says Keith Campbell in CRTKL’s Chicago office.

Airport Cities

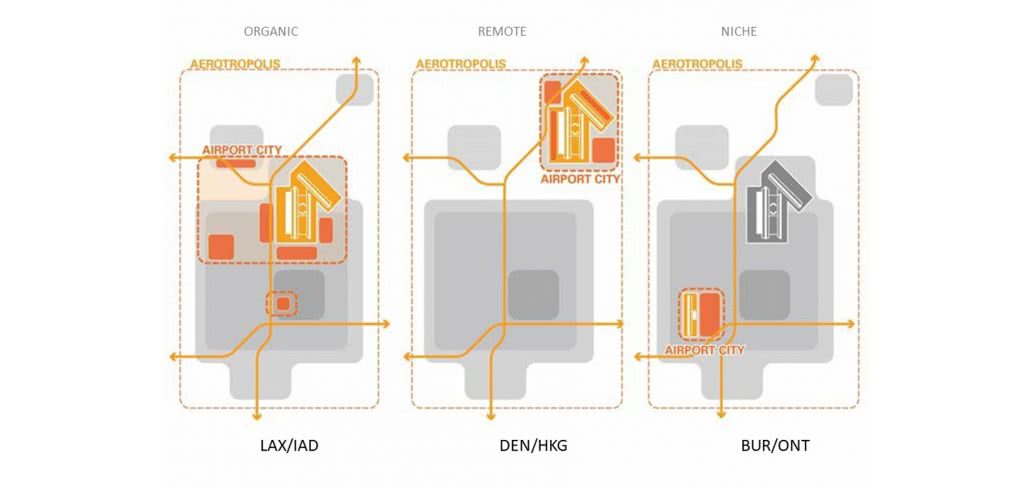

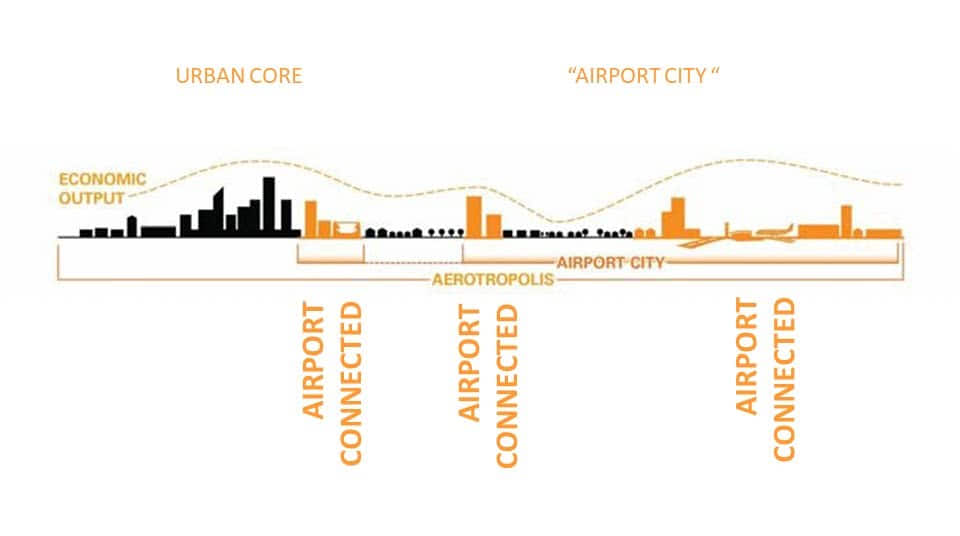

Beyond the corridor-based approach, airports and communities are collaborating to capture value, as well as create mutually beneficial systems of governance, revenue sharing and growth management. Numerous airports have started to structure their growth as part of the community at large.

For example:

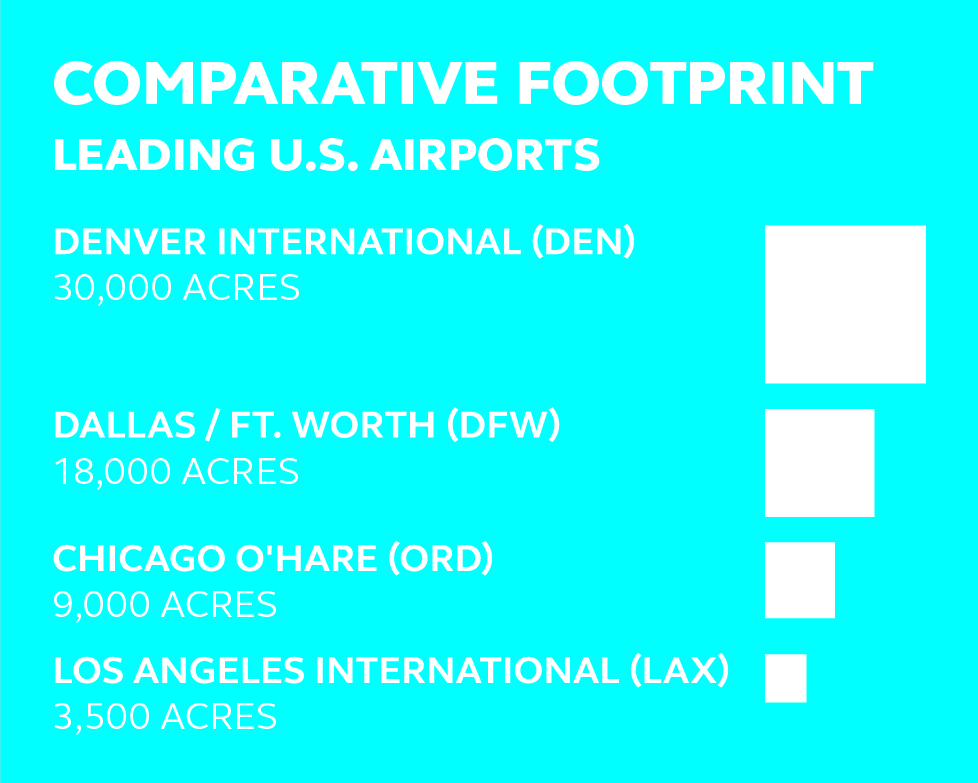

- Capacity — With more than 30,000 acres, four runways and substantial opportunities for growth, Denver International Airport (DEN) is over 10 times the size of Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and has enough land to control its destiny for the foreseeable future.

- High-speed connections and amenities — In addition to centralized security, DEN, ORD and Dulles International (IAD) shuttle passengers to remote terminals via a dedicated underground rail that’s easy to navigate.

- Land management — DEN and Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW) both have significant flexibility in how they develop and manage their land within the airports’ designated areas. They can also land bank using undeveloped land for short-term agricultural or energy uses.

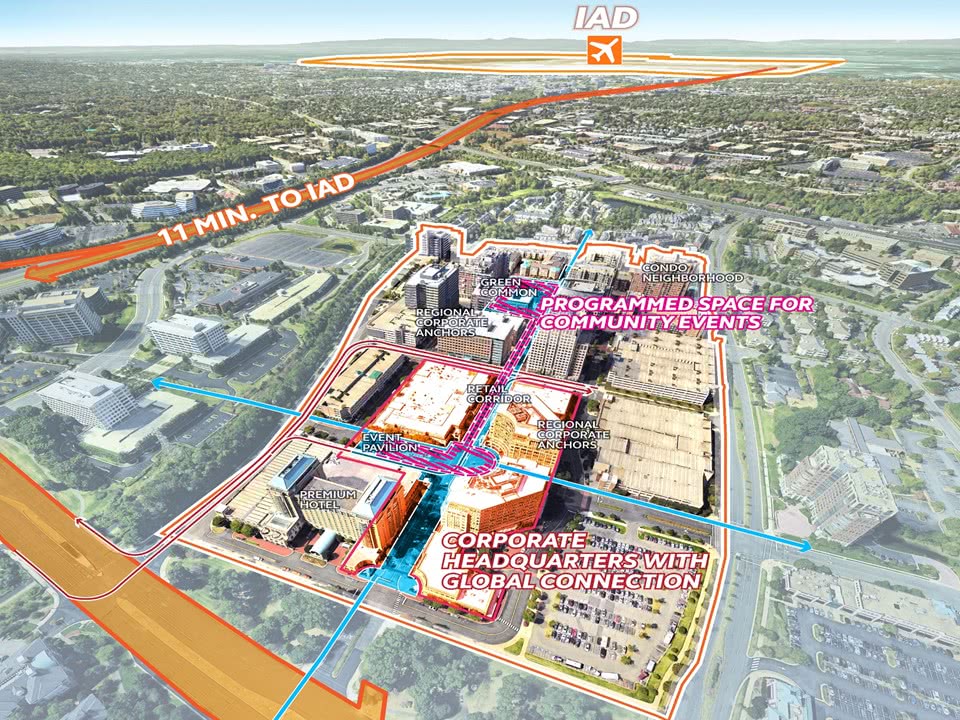

- Experiences — IAD is located close to several mixed-use developments that offer places for visitors, community members, and airport and airline employees to come together and experience the area. “In terms of economic activity, Fairfax and Loudon counties rival that of the District of Columbia, and IAD is the hub that brings a wide range of businesses together. Reston provides a place for all of these interests to collaborate, live, relax and have fun,” says Douglas McCoach, CRTKL’s vice president of Planning and Urban Design, who has worked in Reston for three decades.

Stay tuned for the second in the series of Airports and Communities where we will look at the future opportunities the airports and surrounding communities offer from an urban planner’s perspective.